I have spent the last few years investigating canonical architectures, their ideological inscriptions and what could be said / should be done / may be argued with the medium of film. A blind spot in many discussions in art history. Besides my conceptual and analytical approach, the works I produced were acts of appropriation of space and discourse – a space and discourse to which both the medium of film and myself had not been invited to contribute. The moment the light inscribed itself onto the filmstrip placed in my hand-built cameras, was, at the same time, a technical, a conceptual and a performative act. After making five independently produced films about some of the most prominent Austrian exhibition spaces, ranging from the Vienna Secession and the Austrian Film Museum to the Austrian Pavilion in Venice, I felt like I had said everything I needed to say.

I have been rebelling against the inscriptions and codes of the film-camera, mainly the unit of the single frame. I wanted to get rid of the frame because it is at the core of the representational operations with which I do not agree. That’s why I want my filmstrips not to carry any frames at all. I want to think of the strip’s surface in a more fluid way, to imagine it otherwise, to reconsider the given form, outside of the dominant standardization.

Although I did enjoy the confrontational dialogue with the exhibition spaces I investigated, I also realized I was only referencing architecture made by male figures. Of course, this has more to do with dominant art history than with my artistic approach. I decided to take on a different kind of responsibility. It is time to create filmic architectures / sculptural objects, emphasizing a more queer sensibility.

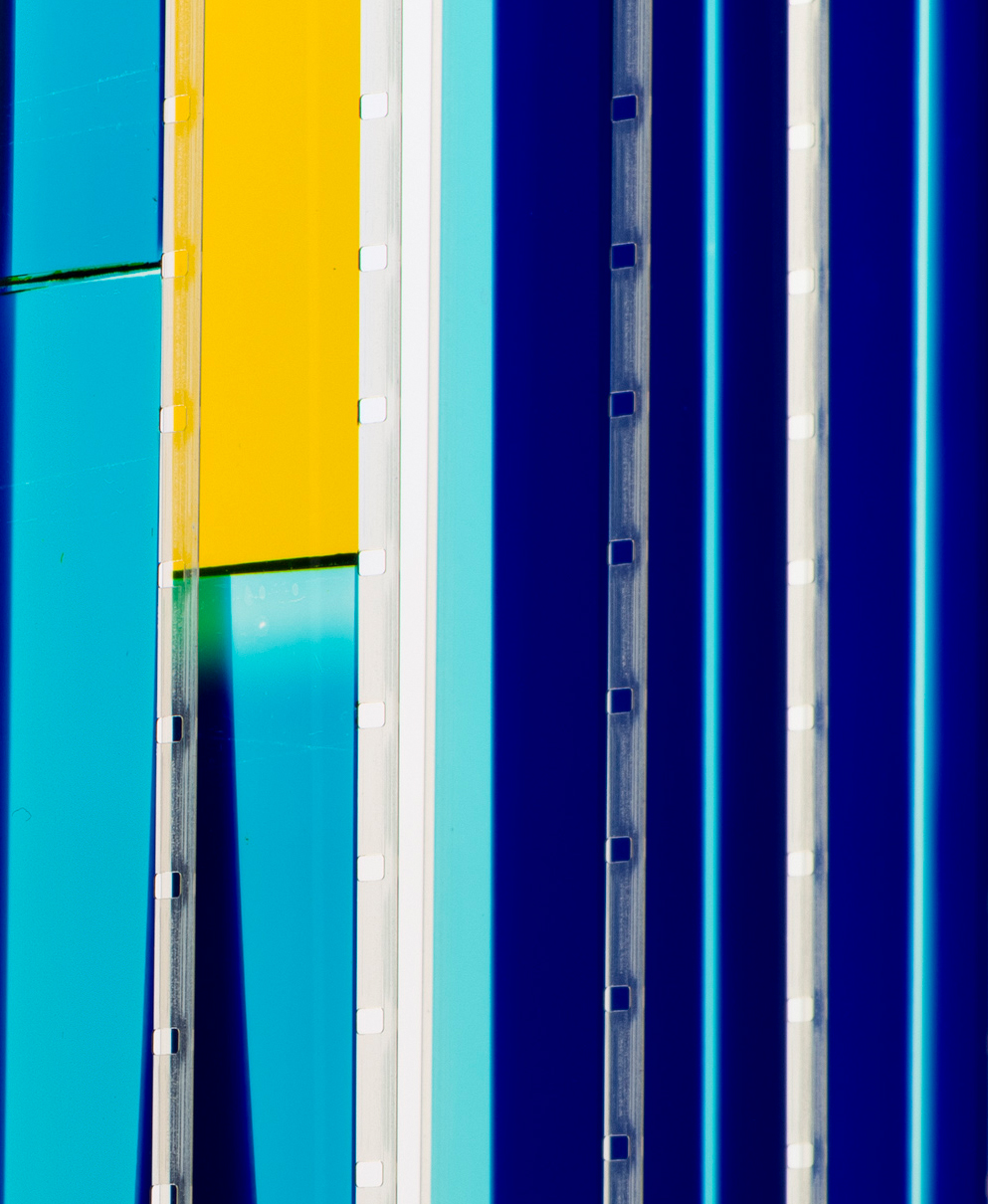

The two film sculptures on display at Wonnerth Dejaco were produced in my studio, where parts of 16mm filmstrips were exposed to different light sources. Various masks were applied on the strips with the intent to shape the light and create specific forms and rhythms. The filmstrips were then integrated into two sculptural objects. It is my very first work entirely made in a studio setting.

Part of one’s art practice is to move forward, to intensify and clarify one’s methodology, but also to react to what has been done and how it could be perceived. My films have often been discussed as being pretty abstract, while I see them as the most concrete films I could possibly imagine. Such a different perception triggers something. I was never interested in abstraction. Somehow, this changed. I now want to find out what abstraction could be about, and what, in particular, queer abstraction might mean.

I enjoy the static power that lies within painting and sculpture, it gives a certain presence, a certain intimacy and urgency in what is articulated. It boldly says „Take this and deal with it!“ As a film artist, it seems utterly daring to fixate one’s concern that way. I could never do it. It is exactly within the element of duration and movement that I want to continue to explore the sensibilities of space and time, concreteness and abstraction, tease, flirt, change, fluidity, interruption, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and openness. Forms of relation and internal discussions. Different states within one entity.

Therefore, abstraction isn’t a shift to avoid representation. Quite the contrary.

Philipp Fleischmann

January 2022

—

Im Lauf der Linie: Philipp Fleischmanns Filmskulpturen

„Die Künstlerin kann auch mittels Linien, die ich als ‚organisch‘ bezeichne, Untersuchungen anstellen, Linien, die als Türen dienen, als Verbindungen zwischen Materialien, als Gewebe etc., um eine gesamte Oberfläche zu modulieren,“1 erläuterte die brasilianische Künstlerin Lygia Clark 1956 erstmals ihren Begriff der „organischen Linie“. Diese manifestiert sich nicht als künstlerisch generierte abstrakte Form, sondern entfaltet sich im Moment der Begegnung, etwa zwischen Bild und Rahmen; sie ist zugleich Zwischenraum oder Leerstelle und Naht oder Klammer. Clarks „organische Linien“ haben ihren Ursprung im architektonischen Raum und in der Materialität von Textilien.

Auf ähnliche Weise wie Clarks „organische Linien“ der Malerei entgegentreten, nähern sich Philipp Fleischmanns Filmskulpturen dem Film: als lebendiges, in der materiellen Realität verankertes Medium. In seinen neuen Arbeiten lässt der Künstler den 16mm-Filmstreifen mittels eines eigens entworfenen, visuell einer Harfe ähnelnden Loopers in Schleifen und über eine wenige Zentimeter schmale Lightbox laufen, bevor der am Boden stehende Projektor Bilder abstrakter Formen an die Wand wirft. Die Linie (des Filmstreifens) begegnet dem Rechteck (des filmischen Bildes) im Raum der Ausstellung.

Fleischmanns 16mm-Filme entstanden im Atelier mittels direkter Belichtung des Filmstreifens, durchaus in Anknüpfung an Traditionen des historischen Avantgardefilms, sogenannter kameraloser „direct cinema“ Experimente – wie etwa jener Stan Brakhages in den 1960er Jahren –, die in die materielle Beschaffenheit des Films intervenierten. Wurden Filme dieser Art gleich dem klassischen Kino auf die Leinwand projiziert, so nahmen die Arbeiten des „Expanded Cinemas“ der 1970er Jahre das gesamte filmische Dispositiv als Verschränkung von Körper und Technik, Material und Bild, Produktion und Projektion in den Blick. Dem Film als temporal-skulpturales Medium widmete sich in diesem Kontext etwa Anthony McCalls Arbeit Line Describing a Cone (1973), bei der der Lichtstrahl des 16mm-Projektors im Laufe einer halben Stunde einen Kreis an die Wand und zugleich einen Kegel in den rauchgefüllten Raum zeichnete.

Fleischmanns Filmskulpturen distanzieren sich jedoch von jenen Versuchen der Entgrenzung des filmischen Mediums. So argumentiert der Künstler weder für noch gegen mediale Spezifität. Vielmehr entwirft Fleischmann eine Topologie des Films, die sich als Ausdehnung und Vervielfältigung des filmischen Materials in dem in Schleifen geführten Filmstreifen räumlich manifestiert. Ähnlich Lygia Clarks „organischer Linie“ produziert jenes Material dort zugleich Leerstellen und Zwischenräume, wo der reale Raum als Negativraum zwischen den vertikalen Lamellen der Filmskulpturen in Erscheinung tritt. Der Filmstreifen bewegt sich als materielle Linie, als welche er dem Medium inhärent ist, zwischen den doppelten Licht- und Bildquellen der Projektionsfläche und der Lightbox. In ihrer intensiven Farbigkeit erscheinen die projizierten Bilder und der beleuchtete Filmstreifen als Endpole einer Bewegung im Raum, die de facto jedoch endlos ist. Nicht der Filmkader als Illusion der Realität, sondern der Filmstreifen als Linie materieller Lebendigkeit.

Bettina Brunner

1 Lygia Clark, Vortrag in Belo Horizonte (1956), zitiert in: Luis Peréz-Oramas, Part 2: Lygia Clark: If You Hold a Stone (2018), https://post.moma.org/part-2-lygia-clark-if-you-hold-a-stone/ (Übersetzung der Verf.).

—

Credits

Displays entwickelt in Zusammenarbeit mit und gebaut von Bert Löschner

Masken realisiert von Anna Haidegger und geschnitten von Gerhard Stocker und Harry Schmidt

Belichtungsapparat konstruiert von Georg Holzmann

16mm Filme belichtet auf Kodak Vision 3 50D, Entwicklung und Kopien: Augustus Color, Rom