I have spent the last few years investigating canonical architectures, their ideological inscriptions and what could be said / should be done / may be argued with the medium of film. A blind spot in many discussions in art history. Besides my conceptual and analytical approach, the works I produced were acts of appropriation of space and discourse – a space and discourse to which both the medium of film and myself had not been invited to contribute. The moment the light inscribed itself onto the filmstrip placed in my hand-built cameras, was, at the same time, a technical, a conceptual and a performative act. After making five independently produced films about some of the most prominent Austrian exhibition spaces, ranging from the Vienna Secession and the Austrian Film Museum to the Austrian Pavilion in Venice, I felt like I had said everything I needed to say.

I have been rebelling against the inscriptions and codes of the film-camera, mainly the unit of the single frame. I wanted to get rid of the frame because it is at the core of the representational operations with which I do not agree. That’s why I want my filmstrips not to carry any frames at all. I want to think of the strip’s surface in a more fluid way, to imagine it otherwise, to reconsider the given form, outside of the dominant standardization.

Although I did enjoy the confrontational dialogue with the exhibition spaces I investigated, I also realized I was only referencing architecture made by male figures. Of course, this has more to do with dominant art history than with my artistic approach. I decided to take on a different kind of responsibility. It is time to create filmic architectures / sculptural objects, emphasizing a more queer sensibility.

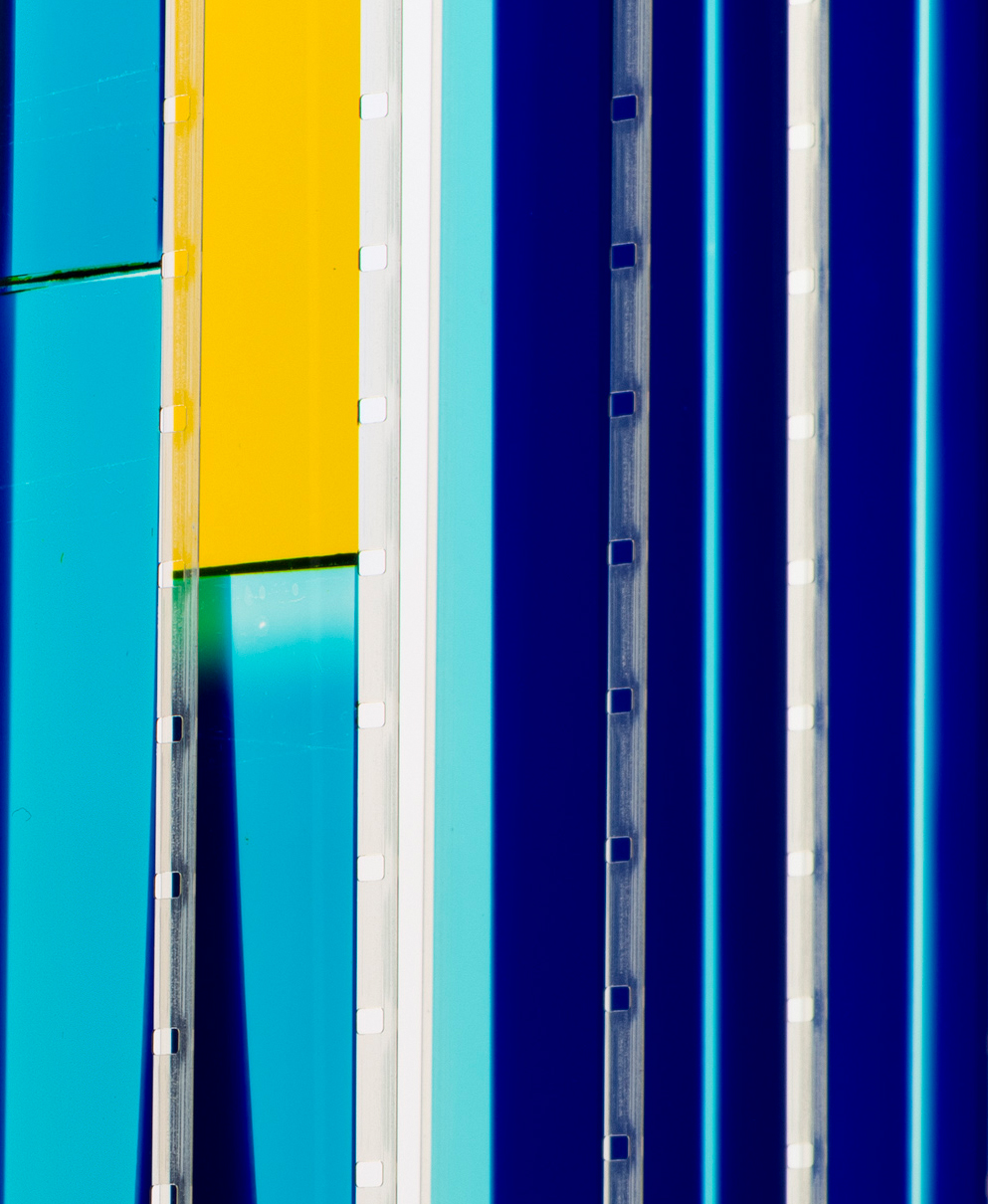

The two film sculptures on display at Wonnerth Dejaco were produced in my studio, where parts of 16mm filmstrips were exposed to different light sources. Various masks were applied on the strips with the intent to shape the light and create specific forms and rhythms. The filmstrips were then integrated into two sculptural objects. It is my very first work entirely made in a studio setting.

Part of one’s art practice is to move forward, to intensify and clarify one’s methodology, but also to react to what has been done and how it could be perceived. My films have often been discussed as being pretty abstract, while I see them as the most concrete films I could possibly imagine. Such a different perception triggers something. I was never interested in abstraction. Somehow, this changed. I now want to find out what abstraction could be about, and what, in particular, queer abstraction might mean.

I enjoy the static power that lies within painting and sculpture, it gives a certain presence, a certain intimacy and urgency in what is articulated. It boldly says “Take this and deal with it!” As a film artist, it seems utterly daring to fixate one’s concern that way. I could never do it. It is exactly within the element of duration and movement that I want to continue to explore the sensibilities of space and time, concreteness and abstraction, tease, flirt, change, fluidity, interruption, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and openness. Forms of relation and internal discussions. Different states within one entity.

Therefore, abstraction isn’t a shift to avoid representation. Quite the contrary.

Philipp Fleischmann

January 2022

—

Following the line: Philipp Fleischmann’s Film Sculptures

“The artist might also investigate by way of lines I’ll call ‘organic,’ lines that function as doors, as connections among materials, as tissues, etc., in order to modulate an entire surface.”1 Brazilian artist Lygia Clark first explained her concept of the “organic line” in 1956. It does not manifest itself as an artistically generated abstract form, but rather unfolds in the moment of the encounter, for example, between image and frame; it is at once an interstice or void and a seam or parenthesis. Clark’s “organic lines” have their origins in architectural space and in the materiality of textiles.

Similar to the way in which Clark’s “organic lines” confront painting, Philipp Fleischmann’s Film Sculptures approach film: as a living medium anchored in material reality. In his new works, the artist arranges the 16mm film strip in loops by means of a specially designed looper visually resembling a harp and lets it run over a narrow lightbox, only a few centimeters in width. Placed on the gallery floor, the projector throws images of abstract forms onto the wall. The line (of the film strip) meets the rectangle (of the filmic image) in the space of the exhibition.

Fleischmann’s 16mm films were made in the studio by means of direct exposure of the filmstrip, quite in keeping with traditions of historical avant-garde film, so-called camera-less “direct cinema” experiments – such as those of Stan Brakhage in the 1960s – that intervened in the material quality of film. Whereas films of this kind were projected onto the screen in the same way as classical cinema, the “expanded cinema” works of the 1970s took the entire cinematic dispositif into consideration as an entanglement of body and technology, material and image, production and projection. In this context, Anthony McCall’s work Line Describing a Cone (1973), for example, dedicated itself to film as a temporal-sculptural medium, in which the light beam of the 16mm projector drew a circle on the wall and, at the same time, a cone in the smoke-filled room over the course of half an hour.

Philipp Fleischmann’s Film Sculptures, however, distance themselves from those attempts to dissolve the boundaries of the cinematic medium. In his works, the artist argues neither for nor against medium specificity. Rather, Fleischmann sketches a topology of film that manifests itself spatially as the expansion and multiplication of the filmic material in the film strip as it is guided in loops through the sculptural display. Similar to Lygia Clark’s “organic line,” this material simultaneously produces voids and interstices where real space appears as negative space between the vertical lamellae of the Film Sculptures. The film strip moves as a material line, inherent to the medium, between the twofold sources of light and image, the projection surface and the lightbox, respectively. In their intense chromaticity, the projected images and the illuminated film strip appear as the end poles of a movement in space. In reality, though, this movement is endless. Not the film frame as an illusion of reality, but the film strip as a line of material liveliness.

Bettina Brunner

(Translated from German)

1 Lygia Clark, conference in Belo Horizonte (1956), quoted in: Luis Peréz-Oramas, Part 2: Lygia Clark: If You Hold a Stone (2018), https://post.moma.org/part-2-lygia-clark-if-you-hold-a-stone/

Credits:

Display devices developed together with and constructed by Bert Löschner

Masks realized by Anna Haidegger and cut by Gerhard Stocker and Harry Schmidt

Exposure device constructed by Georg Holzmann

16mm films exposed on Kodak Vision 3 50D, developed and printed by Augustus Color, Rome