I’ll tell you what I want, what I really, really want, so tell me what you want, what you really, really want.1

Since the mid-1990s, the U.S. television network Nickelodeon has shaped childhood memories with its spectacular live-action shows, animated series and sitcoms, also in German-speaking countries. It existed as a separate station in Germany until 1998, then restarted in 2005 and has been represented on the Austrian market under the name “Nick Austria” since 2006. The commercial network was conceived as a world for and by children as early as the late 1970s, but its great success, global expansion and hyper-commercialization finally came in the 1990s. Since then, thousands of merchandise items, two theme parks and theme hotels have been produced.

The rotating convex mirror at the beginning of Ellen Schafer’s exhibition “Nickelodeon Universe” locates the visitors as those who observe (themselves) and are observed at the same time. Before the eyes of the omnipresent Other, they become part of a universe in which commercial children’s television acts as a metaphor for an all-encompassing neoliberal logic. Perception through the mirror is clouded by an endlessly repeated “I like it… …it likes me,” hand-etched onto the mirror’s front. In reference to a retired Seven Up slogan, Schafer’s “Mirror” marks a relationship to the world that is constituted in consumption and self-affirmation and in which feelings such as satisfaction, pleasure, enthusiasm, or excitement become central categories of action.

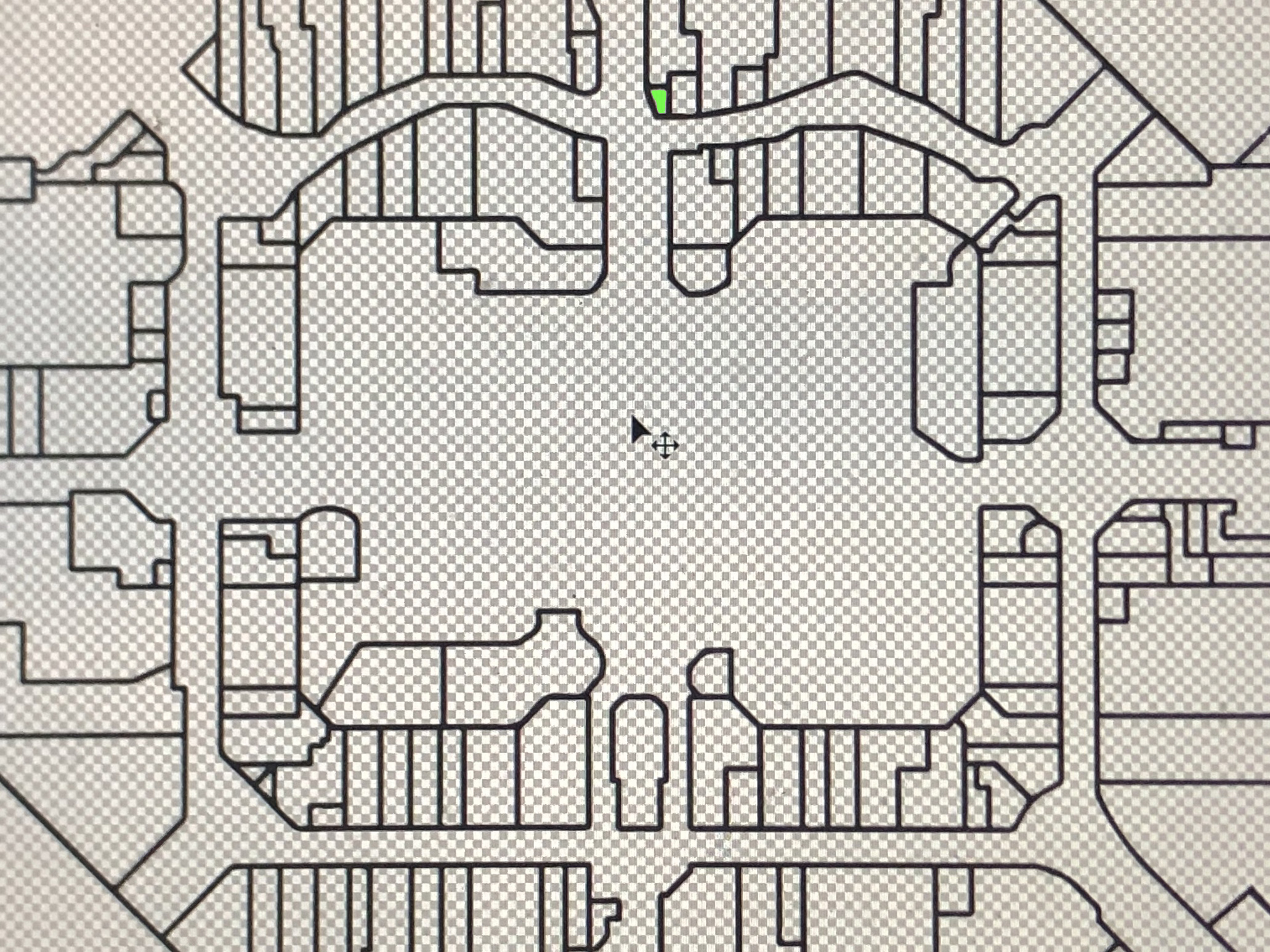

Navigating the world reveals itself as a process of commodification2, in which identity becomes a commodity. For “Billa Plus,” Schafer modified a shopping cart of the now rebranded Merkur supermarket chain and added a plaque engraved with the floor plan of the “Mall of America”, the largest shopping center in the world with 42 million visitors annually. Both the “Mall of America” and the megamall “American Dream,” which opened in New Jersey in 2020 in the midst of the global pandemic feature a “Nickelodeon Universe” amusement park. Schafer herself grew up in 1990s New Jersey, a time when the “end of history”3 was proclaimed and a “capitalist realism”4 was finally taking hold. The Millennials’ experience of being socialized in an all-encompassing marketed lifestyle also finds an expression in Schafer’s wallpaper designed with the brand logos of fictitious sponsors. Though the logos were conceived by the artist, along with graphic designer Ella Gold, they look familiar, citing certain styles that portray companies as unique and are intended to make them recognizable.

The need for uniqueness applies not only to the ostensible authenticity of goods in demand, but also to individual self-presentation. In capitalist realism, the successful endowment of one’s own personality with special things and experiences becomes the guiding principle of a successful life. “Sliming,” which has become an absolute trademark of Nickelodeon, can be understood as such an event. Several celebrities and contestants have been doused with the slimy green mass in various shows. As an individual or collective experience, the act of being slimed can be seen as humiliation in a moment of failure as well as joy and celebration. The popularity of the event led to numerous, purchasable “slime” things, from toys to breakfast cereals to hotels with the option to get “slimed.” The green glow in the second room of the gallery conjures the desire to become part of the society of the “Slime” spectacle. The QR codes on the wallpaper lead to gifs, showing excessively exaggerated stagings of sliming in action.5 In a time in which “subjective fulfillment seems to be a phantasm, which one’s own real life […] can hardly ever catch up with”6, childhood memories of kids of the 90s seem particularly compatible. The infantile characterizes the essence of a “capitalist surrealist” who does not want to “reasonably accept the system, with the option of possibly separating the acceptable from the unacceptable; rather, he wants to take it to extremes”.7 The capitalist surrealist does not feel as an adult who reasonably comes to terms with something, but as a child at play, uninhibited in his urge to experiment and destroy”. Mark Fisher coined the term “depressive hedonia”8 for this condition that manifests itself not as an inability to feel pleasure, as is usual in depression, but on the contrary, as an impossibility of doing anything other than pleasure gratification.

A nickel-plated brass jewelry holder sits as an object on the wall, attached to it is a custom-designed silver-plated chain with the repeating words “Amaze Within a Maze.” It imitates costume jewelry, usually worn with one’s name as a visible accessory. The 90s are emblematic of a time in which the image of limitless possibilities began to crumble.9 Today, rising inequalities and crises with a simultaneous dismantling of certainties conjure up forms of nostalgia, which, however, are mostly not directed at actual events or cultural products, but merely at the consumption of the same. The past becomes quotable and sampleable, making the present appear as an “unstoppable erosion of future”.10 The reflections and fading images of “Esprit !”, “Esprit !!”, “Esprit !!!” express the tension between society’s promise of a good life and the reality in which it finds no fulfillment. Schafer processes the remnants of a consumer culture that is in a state of increasing decay. In her artistic practice, she makes the dissolving of their promises tangible to the senses. She points to how social desires are ceaselessly produced and yet always remain unfulfilled; or as Lauren Berlant puts it, “how fantasies of belonging clash with the conditions of belonging in particular historical moments.”11

Juliane Bischoff

(translated from German)

1 Spice Girls: „Wannabe“, 2:53min, 1996.

2 C. f. Karl Polanyi (1978): The Great Transformation. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp

3 C. f. Francis Fukuyama (1992): Das Ende der Geschichte. München: Kindler

4 Mark Fisher (2013): Kapitalistischer Realismus ohne Alternative? Eine Flugschrift. Hamburg: VSA

5 These can also be accessed directly via the exhibition website designed by the artist: www.slime-time.net

6 Andreas Reckwitz (2020): Das Ende der Illusionen. Politik, Ökonomie und Kultur in der Spätmoderne, Bonn: BpB, p. 204.

7 Markus Metz/Georg Seeßlen (2018): Kapitalistischer (Sur-)Realismus. Neoliberalismus als Ästhetik, Berlin: Bertz + Fischer.

8 Mark Fisher (2006): Reflexive impotence. In: k-punk, 11/04/2006, accessible via: www.k-punk.abstractdynamics.org/archives/007656.html [17/10/2021].

9 C. f. Reckwitz (2020), p. 18f.

10 Mark Fisher (2015): Gespenster meines Lebens. Depression, Hauntology und die verlorene Zukunft. Berlin: Edition Tiamat, p. 24.

11 Earl McCabe (2011): Depressive Realism: An Interview with Lauren Berlant. In: Hypocrite Reader, 6.5: Realism, accessible via: www.hypocritereader.com/5/depressive-realism/ [17/10/2021].