In her first solo gallery presentation in eight years, Maja Vukoje shows new works that thematically tie in with, vary, and further develop some of the groups of works known from her solo exhibition at Vienna‘s Belvedere 21 (December 2020-August 2021).

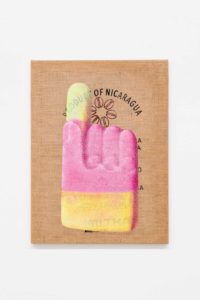

A shared feature of the exhibited works is the material of unprimed, industrially produced burlap. Vukoje uses it as the support for her emphatically reduced compositions, both formally and in view of their motifs. On the level of painting technique, the coarseness of the fabric enables the painter, on the one hand, to push the paint through the stretched burlap from behind, which contributes to the unmistakable plasticity of the paintings. On the other hand, the unfinished surfaces allow the presentation apparatus in the form of the stretcher frame and the wall behind the painting to shine through. In this way, the real space behind the picture surface also becomes part of the pictorial space. Last but not least, the burlap sacks she uses in some of the works also refer to the commodity character of the image itself, as well as to the exploitative relationships in global trade, as Isabelle Graw aptly notes in conversation with the artist.1

For Vukoje, the motifs are also a „special kind of commodity“ freightened with significance2: with paintings such as another Avocado (2023) or Babymelanzani (2023), the artist continues to develop a series in which she depicts exotic fruits in a way that triggers associations with Pop Art, classical portraiture, and still life to the same extent. The cultural history of these products, brought to the consumption of the rich North in global trade via long transport routes, extends far into the colonial era and connects with the history of painting, for example, in the Dutch still lifes of the 17th century.

Similarly, the poppy depicted in McPop (2023) refers to its sad role in colonial past and postcolonial present. Its image is produced using a subtractive technique by bleaching industrially dyed burlap. Different intensities of the use of the chemical bleach result in varied tonalities of the green that lies beneath the black dyeing. Through the delay in the effect, chance enters as an element of design and renders both image carrier and process additionally visible in what Luisa Ziaja perceives as their „performative materiality.“3

Carrying the name „Albers“ in their titles, the works of another series, evident at first glance, represent a homage to a homage. Josef Albers’ Homage to the Square (from 1950) is one of the most influential series of works in 20th century abstract painting. Through her choice of materials, Maja Vukoje’s version expands the famous study of the interaction of color planes by adding several dimensions in one fell swoop. Thus, she creates the interlocking surfaces by applying different kinds of sugar, cocoa, coffee or other commodities that are globally traded in burlap sacks just like the ones that function as the image carriers of the paintings. In this way, her interpretation is „plunging“ Albers’ homage, as Luisa Ziaja puts it, „into multiple complex geographical, material, social, and economic realities,“ contrary to the claim to autonomy of the abstract image of postwar European-North American painting.4

Despite the „postcolonial deconstruction of Pop Art“ rightfully attested to Maja Vukoje’s paintings by Chris Sharp, it would be premature to conclude that the artist is merely concerned with using painting as a springboard for postcolonial critique. For, as Sharp also notes, Vukoje‘s practice investigates the nature of painting itself. No linguistic or material element is used here as a matter of course or without specific purpose – from the translucent burlap that allows the stretching frame to show through to the imprint on the burlap sacks that becomes a pictorial element that extends the meaning of the works. „All of this is to say that the work is fully integrated in that there is ultimately no division or gap between form and content. The political character of Vukoje’s practice is indivisible from the material and formal components of what she does.“5

In her art, Maja Vukoje combines investigations of the conditions of painting with a critique of economic and cultural systems of production and distribution in a globalized world. At the same time, she opens up the internal boundaries of the medium. In her paintings, material, technique, motif and theme tip over, flow into each other, inform each other. By working consistently in the transitional zones of painting along the lines of a critique of postcolonial power relations, Maja Vukoje advances the development of painting as a dispositif of critical cultural production.

1 Isabelle Graw & Maja Vukoje, „Transcultural Withdrawal Strategies on Burlap Sack. A Zoom Conversation,“ in: Stella Rollig/Luisa Ziaja (Ed.), Maja Vukoje, Auf Kante/On Edge (exhibition catalogue, Belvedere 21, Vienna 2020–2021), p. 208.

2 Ibid., p. 208.

3 Luisa Ziaja, „Painterly Illusions und Gestures That Transgress Them,” in: Stella Rollig/Luisa Ziaja (Ed.), Maja Vukoje, Auf Kante/On Edge (exhibition catalogue, Belvedere 21, Vienna 2020–2021), p. 201.

4 Ibid, p. 201.

5 Chris Sharp, “Maja Vukoje’s semi-autonomous paintings,” in: Sandro Droschl (Hg.), MAJA VUKOJE_fuels n’ frumps. Verlag für moderne Kunst Wien, Wien 2017, p. 32–35.