“I shamelessly appropriate everything, everything becomes material for me—even the perishable, the perished, the forbidden juices of life, pulsing.”[1] — Renate Bertlmann

This exhibition brings together the works of three artists who each turned to flowers as the twentieth century came to a close—Renate Bertlmann, Robert Lettner, and Jimmy Wright. In the 1990s, they took up subject matter widely assumed to be cliché, passé, feminine, decorative, pleasure-centric, and unintellectual. In Vienna (Bertlmann, Lettner) and New York (Wright), all three had previously been involved with different 1970s politics and subcultures—feminist, leftist, and gay liberationist, respectively—and they brought these concerns into their later work. Each appropriated and reclaimed the floral still life as a vehicle for staging a larger discussion about painting and power. They all decontextualized and denaturalized their blooms using various material strategies. In their hands, flowers became potent vessels for conversations about language and signification; femininity as excess; and mourning. If floral paintings have traditionally been seen as frivolous and lacking conceptual heft, these practices prove that the decorative is not without concept and that pleasure does not exclude intellect.

Robert Lettner

In Robert Lettner’s 1990 painting Blumen, a mass of vibrant pink and yellow blossoms fill the canvas. Thickly applied strokes of pigment stand in for daisy petals and darting blades of grass. Decontextualized from the larger landscape, the blooms punctuate a teeming field of greenery, forming a kind of floral all-over. Blumen is one of the many large-scale flower works that Lettner painted in the 1990s. While he made black-and-white drawings of the subject at different moments across his career, in the late 1980s, Lettner began to paint floral canvases marked by immersive color and close cropping of the landscape, always painting flowers in full bloom—in the flush of springtime exuberance. Photographs from the time show the artist painting au plein air, as was his practice for making these works—often in Hoffeld, a town about an hour’s drive south of Vienna.[2]

The 1990s flower paintings were an outgrowth of Lettner’s 1988 Landschaft Bilder Therapie exhibition held at Vienna’s Krems-Stein Minoritenkirche. In that show, he showed Hoffeld/Blumengarten, 1987, an early example of the series.[3] Lettner was interested in exploring the landscape as a kind of sign or language. In the Landschaft Bilder Therapie show, every canvas was of a predetermined size and subject and they were installed side by side, making variations in color and composition especially evident. By utilizing repetition and seriality in his paintings of flowers and landscapes, Lettner emphasized “recognizing structures instead of recognizing shapes,” as critic Burghart Schmidt put it in a 1992 article.[4] In the 1990s, Lettner would paint the same landscape again and again, returning annually to capture the same site. “Structural change is my concern in this charged subject,” he explained in a letter from 1995.[5]

For Lettner, subject matter that was considered ornamental or decorative was the ideal vehicle for analyzing the structures of painting—or, “to fundamentally question, research and redefine the tasks, function and purpose of painting,” as scholar Harald Kraemer put it.[6] Speaking of Landschaft Bilder Therapie, Lettner explained: “In the summer of 1988, at the ‘Landscape Therapy’ or LBT exhibition in the aisle of the Minorites’ Church at Stein, everyone thought it was just a form of prettification. And, amusingly, the Abbott of Gottweig was the only person who recognized the symbolic aisle and the return of the ornamental.”[7] Lettner understood ornament as an ideal way of visualizing the very idea of the system or structure—methods by which knowledge is communicated. Ultimately, he believed his installation of serial landscape paintings would call attention to “ways of seeing,” making his exhibition a “vision school” wherein visitors would be taught how to see differently.[8] As psychiatrist Ernst Berger explained in his essay for the Landschaft Bilder Therapie catalogue, “Individual elements of outdated modes of representation are placed in new contexts as ‘quotes’ and in this way express ‘new seeing.’ This makes the change in meaning that the objects have undergone recognizable to us.”[9] While Lettner’s semiotics-informed theorizations of landscape are a way of arming his work against the threat of “prettification,” there is an undeniable subtext of pleasure in this series. Not only are these haptic, sumptuous works deeply pleasurable to look at, but Lettner himself seems to have derived an immense amount of pleasure from making him—taking his paints and canvas out into the Austrian countryside.

Renate Bertlmann

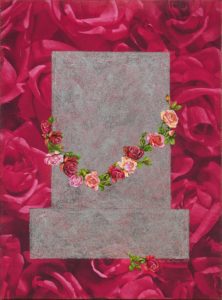

If Lettner avoided the feminine associations of supposedly decorative subject matter, Bertlmann fully embraced them. Rather than painting from life, she used flowers of a more artificial variety—utilizing rose imagery from kitschy paper cut-outs or making photocopies. In her practice, Bertlmann frequently appropriates and plays with loaded symbols, often using kitschy, sentimental material outside the realm of art historical respectability. Bertlmann has a soft spot for using icons tainted with “female triviality,” such as the red rose, a centuries-old symbol of romantic love.[10]

In 1973, Bertlmann anonymously wrote the text for a flyer titled “Why Won’t She Paint Flowers?” put out by the feminist activist group Aktion Unabhängiger Frauen, of which she was a member. Her text excoriated the centuries-old tenet that making pretty little still lifes was the proper outlet for female creativity. She wrote: “Deformed femininity is put in its place, namely that of decorative art. … the journey toward a total emotional liberation and into intellectual clarity will definitely not be undertaken by way of depicting flowers.”[11] Two decades later, Bertlmann ultimately found the appropriation of decorative motifs to be more interesting than their rejection when she not only took up kitschy flower imagery but exaggerated it. Hardly making polite floral paintings, the artist takes sticky sweet, sentimental subject matter and transforms it through different formal methods such as collage, cropping, repetition, enlarging, and bedazzling. In 3 Rosen, 1998, she surrounded a trio of pink roses with repetitive strokes of finger painting. Her bright pink and green daubs of paint were loosely applied and suffused with glitter.

Several other works from 1998 feature different floral motifs and patterns, often enclosed by a border of glitter. In Rosenteppich Farphalle, for example, Bertlmann has superimposed what initially look like glittery butterflies on top of an expanse of roses. Closer inspection reveals that the creatures are actually winged phalluses with knife shaped spikes protruding from their heads. Erinnering is a petite, almost cloying composition that looks like bedroom art, a collage made by a teenage girl. Playing with the convention of “copy art,” the artist placed a photo of herself as a child over a pattern of roses printed on colored foil. In another work of “copy art” Amo ergo sum, Bertlmann wrote the titular phrase along the edges of a color copy of a rose bloom. “Amo ergo sum” is a phrase that has driven Bertlmann’s work for the past 25 years, including in her 2019 presentation at the Austrian pavilion in the Venice Biennale. Writing in the catalog for that exhibition, scholar Beatriz Colomina explained: “AMO ERGO SUM, I love therefore I am. The counter to Descartes’s cogito ergo sum, I think therefore I am. But love is not simple. It has never been. It will never be. Only in soapy, sugary novels and films. Uninteresting, unreal. There is no knowledge without pain. Love is harder than thought.”[12] Bertlmann’s love of kitsch is not only conceptual or aesthetic, it is also about emotion and lived experience. As the artist put it: “I admit my bad taste, I love kitsch because it is so dense, dense with feelings and imagination.”[13]

Jimmy Wright

Like Bertlmann, Wright also sees kitschy flower images as vehicles for feeling. Describing his floral works, he explained, “they’re images from within, rendered with skills learned from observation.”[14] After spending the 1970s making sketches of the characters populating underground gay spaces, Wright turned to flowers in the late 1980s when his partner Ken Nuzzo was diagnosed with HIV. Faced with Ken’s slowly deteriorating health, Wright turned to floral still lifes as a method of coping, finding comfort in the rote task of painting from observation. Plucking two large canvases from a dumpster and using decaying sunflowers as his subject, Wright spent several years in the studio on a single task. Two monumental paintings emerged from this period—Flowers for Ken, Sunflower Stem, 1988-1991 and Flowers for Ken, Sunflower Head, 1989-92—which were completed around the time of Ken’s death in 1991.

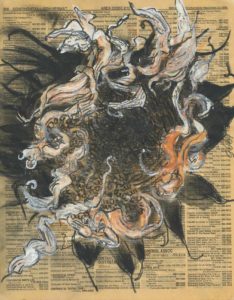

In the ensuing years, Wright continued to draw and paint flowers, often using them to memorialize loved ones who died of AIDS. In the series Sunflower Phonebook Momento Mori, 1993-95, Wright made more than 90 pastel drawings on pages from the 1989 New York City phonebook, frequently on the page that held the deceased friend’s contact information. Wright’s pastel flowers are in the process of decay, a state heightened by the artist’s black-and-white palette. The long, spindly petals of Wright’s flowers curl and flip, giving a dynamic sense of movement to the tangled mass of black strokes that mass around the sunflower’s large head. In No. 9, several tall stalks overlap, while No. 12 features a single blossom blowing in the wind. No. 7, a more colorful and detailed iteration, crops closely in on the spiral florets of the flower’s center.

In larger pastel drawings from the same period—Sunflower 10 and 11, 1994—Wright draws the same bloom from both the front and the back. Similarly decontextualized from a natural setting, the long stalks sit against a field of white paper. Using faded tones of yellow, orange, brown, and green, Wright has carefully captured the complex tones and textures of its withered leaves and petals. Because he understands painting’s repeated motifs and clichés, Wright ueses the floral still life as a powerful medium for themes of obsolescence, pain, and memorialization. As the artist put it: “I am primarily interested in how an inanimate substance such as oil paint can in certain situations become the repository and signifier of human emotions.”[15]

Ashton Cooper

[1] Renate Bertlmann and Felicitas Thun-Hohenstein, “The Vicissitudes of Life Have Washed Us to Each Other’s Shores: L’Associedaire de R & F” in Discordo Ergo Sum: Renate Bertlmann (Vienna: Verlag Fur Moderne Kunst, 2019), 46.

[2] Harald Kraemer, Robert Lettner: Das Spiel Von Kommen Und Gehen (Ritter Klagenfurt, 2018), 157.

[3] Ernst Berger, Landschaft Bilder Therapie: Robert Lettner 1982 bis 1988 (Vienna: Amt der Niederosterreichischen Landesregierung Abt.111/2, Kulturabteilung, 1988), 36.

[4] “Dennoch geht es Lettner um etwas anderes, wie Burghart Schmidt 1992 in seinem Beitrag »R. Lettners Blumenwiesen zu Wasser und zu Lande und in der Abstraktion« dargelegt und hierbei die Frage aufgeworfen hat: »[ … ] warum es denn notig sein sollte, im Bild etwas wiederzuerkennen, etwa die Seerosen oder die anderen Blumen, das Wasser oder die Blatter, wo es doch um die Erkenntnis von Strukturen statt des Wiedererkennens von Gestalten geht.«” Kraemer, 71.

[5] »Das Format der Originale ist 100 x 95 cm. Die Bilder 1-4 entstanden 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994 und sind Jahr fiir Jahr an derselben Stelle als Freilichtmalerei in 01 auf Leinen geschaffen worden. Die strukturelle Veranderung ist mir bei diesem belasteten Thema das Anliegen und es versteht sich von selbst, daB ich an dieser Serie weiterarbeiten werde.« Kraemer, 71.

[6] »In den rund 90 Olgemalden dieser LBT-Serie zeigt sich die Vielfalt in Licht und Farbe, Komposition, Raum und Struktur von denen R. Lettner immer wieder ausging, um Aufgaben, Funktion und Zweck der Malerei grundlegend zu hinterfragen, zu erforschen und neu zu definieren. « Kraemer, 70.

[7] Robert Lettner, “Robert Lettner in Dialogue with Harald Kraemer” in Robert Lettner In Dialogue with the Chinese Landscape (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Museum and Art Gallery, 2017), 42.

[8]Berger, 9; Kraemer, 204.

[9] Berger, 9.

[10] Helga Kampf-Jansen, “ALS DIE KUNST DEN KITSCH NOCH NIGHT VEREINNAHMT HATTE: Eine kurze Gedankenskizze zu einem langeren ProzeB,” 15.

[11] “Why Won’t She Paint Flowers?” in Discordo Ergo Sum: Renate Bertlmann (Vienna: Verlag Fur Moderne Kunst, 2019),353.

[12] Beatriz Colomina, “Wars of Roses” in Discordo Ergo Sum: Renate Bertlmann (Vienna: Verlag Fur Moderne Kunst, 2019), 84.

[13] Renate Bertlmann, “Obsession, Protest, Spirituality: An Interview with Renate Bertlmann, by Gabriele Schor,” in Renate Bertlmann: Works 1969 – 2016 (Vienna: Prestel Verlag, 2016), 32.

[14] Sarah Buhr, Jimmy Wright: Twenty Years of Paintings and Pastels (Springfield: Springfield Art Museum, 2009), http://www.jimmywrightartist.com/essays/sarah-buhr/.

[15] Buhr.