Saskia te Nicklin, Version 3

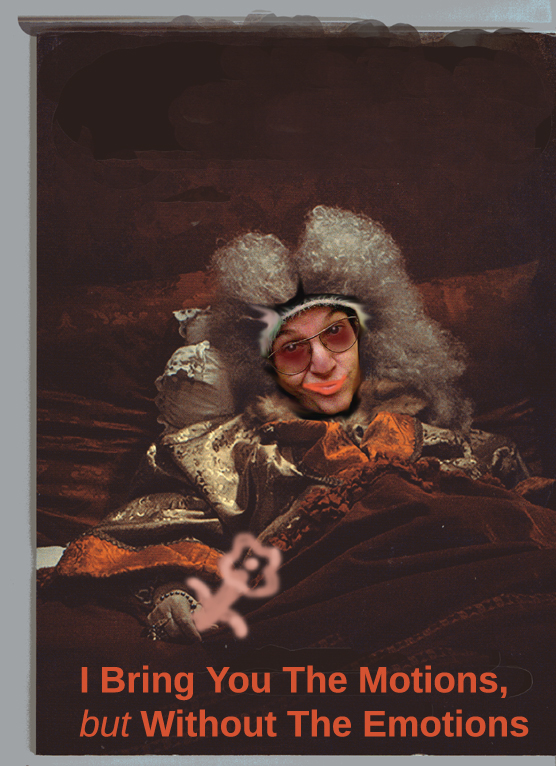

Written for the exhibition I’ll give you the motions without the emotions or Grafting bone with dirt (to be decided)

I have been struggling with this text for a while. Saskia pretty much seems to know what she wants: It is somewhere in the intersection between the lyrics of Laurie Anderson’s Language Is A Virus From Outer Space (“Paradise is exactly like / Where you are right now / Only much, much better”) and a general fear of TikTok and the like. I keep thinking about The Animal’s version of Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood, but as a self-fulfilling prophecy, Saskia doesn’t get me. Me being a friend and a fellow artist turned unpublished author.

We talked a bit about “I” prior to writing this. It’s paradoxical to be an exhibitor, who wants to stay private. We both want our selves to be washed away out of sight from the art works. Saskia thinks of it as placing a mirror with no reflections. I think that paradoxes in general mainly belong in language, but since we probably can’t perceive anything without it (language), it might as well be that they exist in their own nature.

The first version of the text was like this:

Saskia te Nicklin

Written for the exhibition Grafting bone with dirt

What does te stand for? It does not matter. It is without a capital letter, airy, as if it has neither beginning nor end – a kind of pause for thought in the middle of the name. One who clears her throat perhaps, or who stutters a little. A mocking snort of sorts. Saskia herself is also without beginning and end. That is to say, she began in Copenhagen, but came from parents who were a bit extraterrestrial and flickery themselves. They cut their roots in the sixties, grew anew from the kaleidoscope of bodies made free and perhaps not so free after all, of substances meant to stimulate and expand the view on the world, gender, and life, of garish colours in basement rooms. In that way, there was no real beginning – Saskia became a prolongation, like everyone else, of her parent‘s pursuit. She stretches the past with her into the present, but she does not understand the times we live in. In Vienna, she goes from playground to playground, on trips to parks and nearby forests with her two young children, who are now engaged in commencing a life, stretching their mother’s search with them further into life. What do you pass on to such new people? What did she herself get from her parents? She looks back at the tracks that have been left behind, they stand out now and then when the light hits just right, like the slime trail of a snail that has slowly but surely wet its own way forward, always forward.

It continued like this:

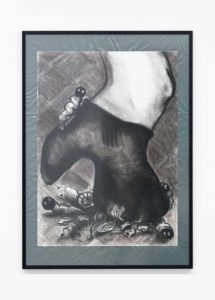

Saskia experiences an overwhelming Weltschmerz from time to time. The pencil lines become passive aggressive and the stupid faces sarcastic. She is searching for tenderness, but a human being is a pile of flesh and bacteria, she thinks. Nature is violently disordered, complex beyond all comprehension, alive and dangerous. Animals, plants, bacteria and fungi live in fierce and soft symbioses with each other, people go around idiotically creating parks, hedges to separate city from nature, lawns to relax on, apps to guide meditation towards an authentic and relaxed self.

She is working on a picture with a mother figure vomiting into a child’s mouth. What we throw up, she thinks, is what we cannot digest ourselves. There is an early form of learning where we absorb our parent’s lack of knowledge and understanding of the world. And there comes a time when we regurgitate our lack of knowledge and understanding into the open mouths of our own gorging children. When we leave home we discover that nature exists somewhere outside the rhetorical realm. We discover that we have many words, but that we lack a language. From generation to generation, we have piled on top of our predecessor, piled higher and higher. We have created growth that way and some sort of overview, but we have gotten further away from the starting point. The human tower is rickety and rotting from below. Heritage and environment are becoming more and more sloshed masses.

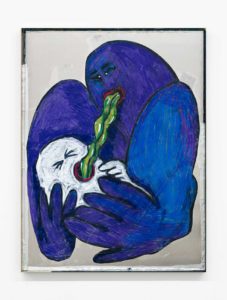

In another painting she uses metal lacquer to make dense colour fields, a simplified landscape that suits an undifferentiated view on nature. On top of that a large drawing of a couple is mounted – a strong looking human figure licks another figure on top of its skull faced head. Nature is also removed from its origin when it is created by humans: Nature must be the reality that gives birth to itself, that exists independently of us. We have taken an unnatural control and turned death and birth inside out. We are now giving birth to ourselves. Nature has become a longing for something that existed before us, something that might still exist within us if we look long enough. We crawl into ourselves at the risk of imploding. Nature becomes a rhetorical concern, dealing with what is good and beautiful and its opposite: Ourselves as evil, ugly and wrong. We are creatures who long to be away from ourselves.

It ended more or less this way:

Her view of humanity becomes a bong from which we take turns sucking. The smoke first scratches the throat, then the lungs, and then it spreads into the blood. It is the past and the future that blend like active substances, creating the present thereby. The small, but exempt te insists on being there without meaning or direction.

In Version 1 Saskia was concerned that she was being exposed – it did not matter so much whether or not the Saskia in it was generic, what mattered was this: As we (as humans) become more and more plastic we see nature as being malleable as well. Most of all, she says, it is the distance to reality that chocks her. She fears for the younger generations who seem to have embraced the influencers – the door-to-door-salesmen of our days – as teachers on life, priests, or gods even. Is this where youth seeks answers, reflections and belonging?, she asks.

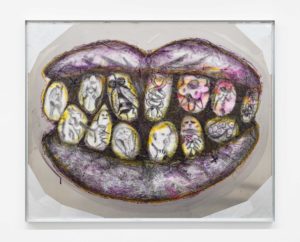

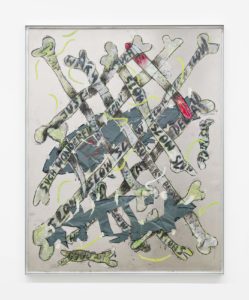

What I notice is, that the more I try to bring Saskia unwillingly in to the text the more I have to carry that myself, forcing me to be present as well. In a bizarre dance writing back and forth we have steadily forced ourselves to become involuntary part of the exhibition text so that in the end I do not exactly recognize who is who and why. I do know, however, that I find it to be fitting to the exhibition – that Saskia’s transferring of drawings unto pealed off layers of glue, her drawings of words on a grotesque smile, pink blank hands on fried egg plants, things like that, challenge and evoke emotions and intellectual stabs. I, for one, think that there is a rich pool from the sixties and seventies that she has soaked up, now seeping out ideas about transcendence and the self as a much contested battlefield. It seems to me that she is questioning humanity, but in a very fleshy manner, that nature lies right underneath her visual language.

Ditte Soria, 2022