We all have one. In every dwelling, whether a one-room apartment, sprawling mansion, or houseboat, there’s always a solitary cupboard full of junk. If you’re lucky, it stays in place, if not, it tends to spread outwards, covering kitchen sides and windowsills, vanity tables and bookshelves. In his 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Philip K. Dick calls this stuff “kipple.” For the sci-fi author, kipple is “useless objects, like junk mail or match folders after you use the last match or gum wrappers or yesterday’s homeopape,” which, “when nobody’s around… reproduces itself.”

In the post-apocalyptic setting of this novel, kipple stands as a metaphor for the rapid deterioration of the Earth. In contemporary society, however, the opposite is true. Junk is bad, yes, but free gifts, single-purpose appliances, and limited-edition products? These are seen as evidence of a functioning, nay, prosperous, civilization. Or as Georg Petermichl puts it, “the idea is that there is constantly a surplus. You buy something and you get a bit more and that’s seen as ‘progress.’”

Fascinated by the hold these kinds of consumer goods have over us, the genesis of the artist’s exhibition at Wonnerth Dejaco is the humble Coca-Cola glass. Like kipple, this branded freebee, which has been produced in various colours, shapes, and sizes over the years, has no inherent value but can be found in homes around the world. For Universal Thoughts: Ambiguous Plus, Petermichl has taken some of these glasses—McDonald’s giveaways found “standing around” at his parent’s house—and used them to produce a new series of ceramic vases, collectively titled Clash. Made from pressing these objects into wet clay, the glass melts during the firing process, leaving a barely recognizable mass that juts out uncomfortably from a hole in the finished vase.

This is not the first time that Petermichl has used ceramics in his work. For the 2017 series Schlüsselwerke 2011- (Keyworks 2011-), the artist made a group of vases featuring imprints of keys copied from his previous studios, as well as various galleries and project spaces where he’s exhibited artwork. By stamping elements of his professional life onto antique forms, some of which were inspired by pieces in the collection of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, Petermichl not only merged two eras but also two types of value: In a museum, the merit of an object sitting on a plinth largely goes unquestioned, whereas the “worth” of an emerging artist is under constant negotiation.

In these new pieces, Petermichl continues using shapes taken from the collections of art and design museums, but this time in combination with consumer goods. The collision of these two forms, different as they may appear, brings up unexpected parallels between them, namely that both types of objects are functional in nature. “They were created to fulfil a purpose,” Petermichl explains. “The vases, like the Coca-Cola glasses, were intended to carry water, not to stand behind security glass.” The difference, of course, is that one set of objects has limited value—although described as “collectables” Coca-Cola glasses retail for less than 50 dollars on eBay—whereas age and rarity have rendered the other priceless.

The idea that objects accrue value over time is playfully questioned in two large-scale neon sculptures, key (2017) and key (2020). Visitors familiar with the Viennese art scene might recognize the first of these works from the entrance to New Jörg, where it’s been hanging since Petermichl did a show there three years ago. Brought in from the cold, the neon key—copied from the set to the artist’s studio at that time—now shows clear signs of age. In comparison, the second of these works, its form taken from the key to Wonnerth Dejaco, has been newly produced for the exhibition. As with the artist’s previous key works, these replicas reflect moments that the artist felt were important to his career or artistic practice.

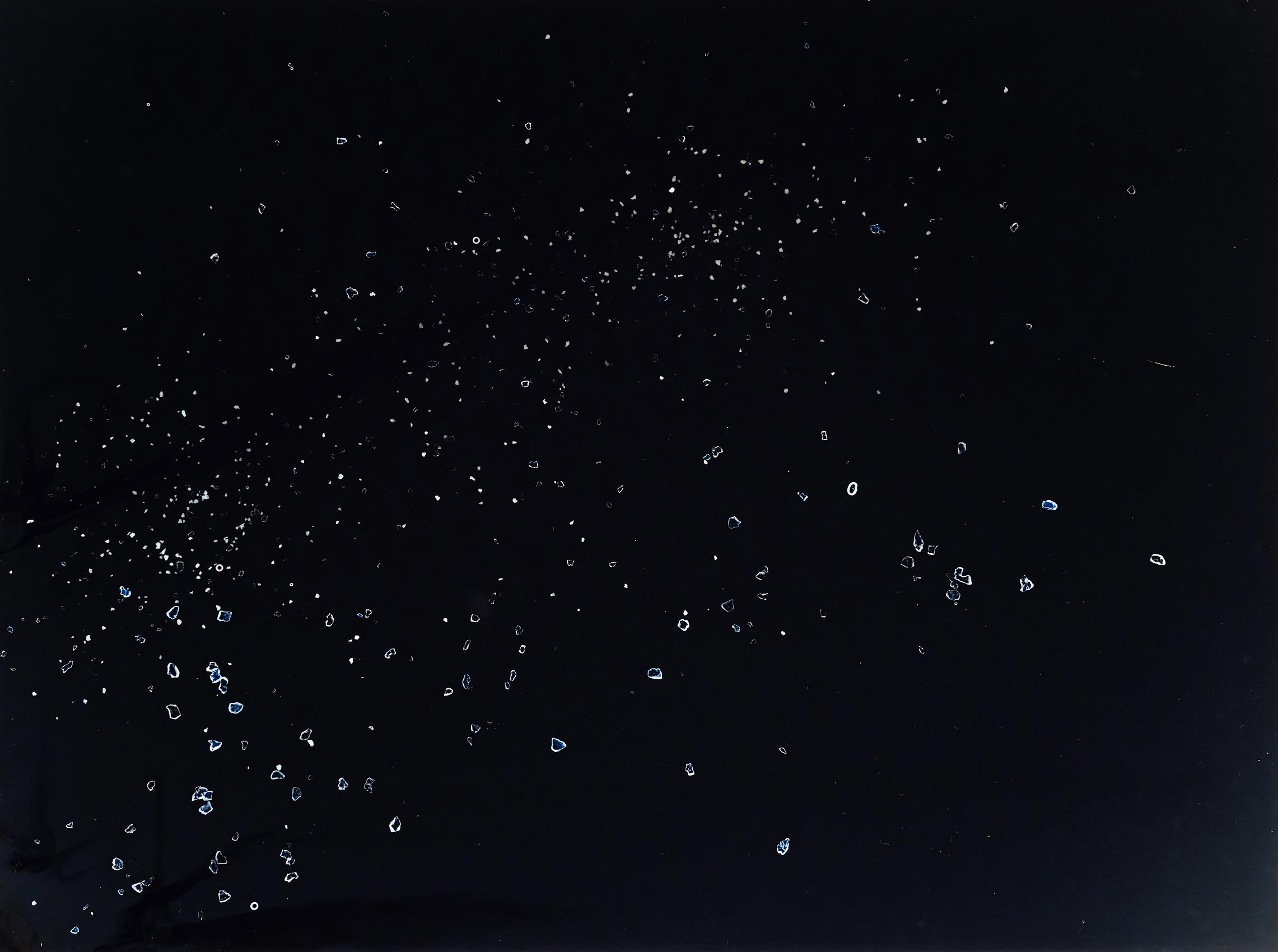

Returning to the “plus” in the exhibition’s title, new photograms feature the shapes of silica gel pieces that have been scattered across the paper’s light sensitive surface. Normally added to products to keep them dry, silica gel is just one of many materials used to protect consumer purchases that cannot be recycled, a phenomenon that Petermichl coyly reflected on in a previous project in which he created a series of photograms using bubble wrap and airbags he received with his online purchases. Although he doesn’t see himself as a political artist per se, the “ambiguous” nature of these transactions, to return again to the show’s title, can be seen to come from the mixed feelings one gets when receiving this kind of packaging. In our society the joy of receiving more stuff is often tainted by thoughts of plastic trash islands in the ocean or the depletion of the Amazon rainforest.

Finally, the differing levels of value at play throughout the exhibition come together in nail, 2020, a ceramic sculpture of a used nail. Like the key, this everyday object has an oversized role in artistic production – “A nail has the potential to be part of something greater than itself,” Petermichl remarks, “something very artistic and beautiful”—but once its use value is exceeded it is easily cast aside. Placed in front of an empty light box that might itself be called upon to house a Jeff Wall or a Coca-Cola advertisement, here the boundaries between artwork, antique object, everyday item, consumer product, or kipple are merged once and for all.

Chloe Stead is a writer and editor based in Berlin.